About IRAN

Fast Facts

Name of the country: | Islamic Republic of Iran |

National Slogan: | Independence, Freedom, Islamic Republic |

Capital: | |

Geographical condition: | 35 41 N 51 25 E |

The largest city: | Tehran |

Language: | Persian |

State religion: | Islam |

Leader: | |

President: | |

National Day: | 11 February |

Population: | 83.075.000 (2019) |

Currency unit: | Iranian Rial |

Internet Domain: | .ir |

International Tel Code: | 0098 |

Exports: | oil, carpet, fruits, dry fruits (pistachios, raisins and dates), leather, caviar, petrochemical products, apparels and dresses, foodstuffs. |

Imports: | machineries, industrial metals, medicines, chemical derivatives. |

Industries: | oil, petrochemical, textile, cement and other materials for building construction, food derivatives (especially refining sugar and extracting edible oil). |

Agriculture: | wheat, rice, grains, fruits, oily seeds such as pistachios, almond, walnut, cotton. |

Transportation: | 7286 kilometers of railways and 158000 kilometers of roads. |

Pipelines: | oil derivatives 3900 kilometer, natural gas 4550 kilometer. |

Ports: | Abadan, Ahwaz, Shahid Beheshti port, Abbas port, Anzali port, Bushehr port, Imam Khomeini port, Mahshahr port, Turkman port, Khoramshahr, Noshahr. |

Geography

Iran is a county in southwest Asian, country of mountains and deserts. Eastern Iran is dominated by a high plateau, with large salt flats and vast sand deserts. The plateau is surrounded by even higher mountains, including the Zagros to the west and the Elburz to the north. Its neighbors are Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan and Armenia on the north, Afghanistan and Pakistan on the east, and Turkey and Iraq on the west. Tehran is the capital, the country's largest city and the political, cultural, commercial and industrial center of the nation. Iran holds an important position in international energy security and world economy as a result of its large reserves of petroleum and natural gas.

Climate

Iran's climate ranges from arid or semiarid, to subtropical along the Caspian coast and the northern forests. On the northern edge of the country (the Caspian coastal plain) temperatures rarely fall below freezing and the area remains humid for the rest of the year. Summer temperatures rarely exceed 29 C (84.2 F). Annual precipitation is 680 mm (26.8 in) in the eastern part of the plain and more than 1,700 mm (66.9 in) in the western part. To the west, settlements in the Zagros basin experience lower temperatures, severe winters with below zero average daily temperatures and heavy snowfall. The eastern and central basins are arid, with less than 200 mm (7.9 in) of rain, and have occasional deserts. Average summer temperatures exceed 38 C (100.4 F). The coastal plains of the Persian Gulf and Gulf of Oman in southern Iran have mild winters, and very humid and hot summers. The annual precipitation ranges from 135 to 355 mm (5.3 to 14.0 in).

https://www.visitiran.ir/climate

History

Recent archaeological studies indicate that as early as 10,000 BC, people lived on the southern shores of the Caspian, one of the few regions of the world which according to scientists escaped the Ice Age. They were probably the first men in the history of mankind to engage in agriculture and animal husbandry.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Art & Culture

Language and literature

Article 15 of the Iranian constitution states that the "Official language (of Iran) is Persian and the use of regional and tribal languages in the press and mass media, as well as for teaching of their literature in schools, is allowed in addition to Persian." Persian serves as a lingua franca in Iran and most publications and broadcastings are in this language.

Next to Persian, there are many publications and broadcastings in other relatively popular languages of Iran such as Azeri, Kurdish and even in less popular ones such as Arabic and Armenian. Many languages originated in Iran, but Persian is the most used language. Persian belongs to Iranian branch of the Indo-European family of languages. The oldest records in Old Persian date to the Achaemenid Empire, and examples of Old Persian have been found in present-day Iran, Iraq, Turkey and Egypt. In the late 8th century, Persian was highly Arabized and written in a modified Arabic script. This caused a movement supporting the revival of Persian. An important event of this revival was the writing of the Shahname by Ferdowsi (Persian: Epic of Kings), Iran's national epic, which is said to have been written entirely in native Persian. This gave rise to a strong reassertion of Iranian national identity, and is in part credited for the continued existence of Persian as a separate language.

Persian is spoken today primarily in Iran, Afghanistan and Tajikistan, but was historically a more widely understood language in an area ranging from the Middle East to India, significant populations of speakers in other Persian Gulf countries, as well as large communities around the World.

Persian is a subgroup of West Iranian languages that include the closely related Persian languages of Dari and Tajik; the less closely related languages of Luri, Bakhtiari and Kumzari; and the non-Persian dialects of Fars Province. Other more distantly related languages of this group include Kurdish, spoken in Turkey, Iraq, and Iran; and Baluchi, spoken in Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan. Even more distantly related are languages of the East Iranian group, which includes Pashtu, spoken in Afghanistan; Ossete, spoken in North Ossetian, South Ossetian, and Caucusus of former USSR; and Yaghnobi, spoken in Tajikistan.

Other Iranian languages of note are Old Persian and Avestan (the sacred language of the Zoroastrians for which texts exist from the 6th century B.C.). West and East Iranian comprise the Iranian group of the Indo-Iranian branch of the Indo-European family of languages.

Indo-Iranian languages are spoken in a wide area stretching from portions of eastern Turkey and eastern Iraq to western India. The other main division of Indo-Iranian, in addition to Iranian, is the Indo-Aryan languages; a group comprised of many languages of the Indian subcontinent, for example, Sanskrit, Hindi/Urdu, Bengali, Gujerati, Punjabi, and Sindhi. Scholars recognize three major dialect divisions of Persian: Farsi, or the Persian of Iran, Dari Persian of Afghanistan, and Tajik, a variant spoken in Tajikistan in Central Asia. We treat Tajik as a separate language, however.

Farsi and Dari have further dialectal variants, some with names that coincide with provincial names. All are more or less mutually intelligible. Persian in Iran and Afghanistan is written in a variety of the Arabic script called Perso-Arabic, which has some innovations to account for Persian phonological differences. This script came into use in Persia after the Islamic conquest in the seventh century. A variety of script forms: Nishki is a print type based closely on Arabic; Talik is a cultivated manuscript, with certain letters having reduced forms and others occasionally elongated in order to produce lines of equal length; and Shekesteh is also a manuscript, allowing for a greater variation of form and exhibiting extreme reduction of some letters Persian, until recent centuries, was culturally and historically one of the most prominent languages of the Middle East and regions beyond. For example, it was an important language during the reign of the Moguls in Indian where knowledge of Persian was cultivated and encouraged; its use in the courts of Mogul India ended in 1837, banned by officials of the East Indian Company (British Colonialism).

Persian scholars were prominent in both Turkish and Indian courts during the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries in composing dictionaries and grammatical works. A Persian Indian vernacular developed and many colonial British officers learned their Persian from Indian scribes.

The name of the modern Persian language is sometimes mentioned as Farsi in English texts.

https://www.visitiran.ir/art-culture

Poetry

Human beings are members of a whole, In creation of one essence and soul. If one member is afflicted with pain, Other members uneasy will remain. If you have no sympathy for human pain, The name of human you cannot retain. These verses by great Iranian poet Sheik Sadi is written in entrance to the Hall of Nations of the UN building in New York.

We can distinguish two periods of Persian poetry: one traditional, from the tenth to nearly mid, twentieth century; the other modernist, from about World War II to the present. Within the long period of traditional poetry, however, four periods can be traced, each marked by a distinct stylistic development. The first of these, comprising roughly the tenth to the twelfth century, is characterized by a strong and an exalted style (sabk-e fakher). One may define this style (generally known as Khorasani, from the association of most of its earlier representatives with Greater Khorasan) by its lofty diction, dignified tone, and highly literate language. The second, from the thirteenth to the fifteenth century, is marked by the prominence of lyric poetry, the consequent development of the ghazal into the most significant verse form, and the diffusion of mystical thought. Its style is generally dubbed Eraqi because of the association of some of its earlier exponents with central and western Persia (even though its two major representatives, Sadi and Hafez, were from the southern province of Fars); it is known by its lyric quality, tenderness of feeling, mellifluous meters, and the relative simplicity of its language.

The third period, which extends from the fifteenth well into the eighteenth century, is associated with the Indian style of Persian poetry (sometimes called Isfahani or Safavi). It has its beginning in the Timurid period and is marked by an even greater prominence of lyric poetry, although it is somewhat devoid of the linguistic elegance and musicality of the preceding period. The poets of this period often busied themselves with exploring subtle thoughts and far fetched images and elaborating upon worn-out traditional ideas and metaphors. The fourth period, from approximately the eighteenth to the mid-twentieth century, is known as the Literary Revival (bazgasht-e adabi).It features a reaction against the poetic stagnation and linguistic foibles of the late Safavid style, and a return to the Eraqi style of lyric poetry and the Khorasani style.

With Ferdowsi's immortal poem, the Shah-nama, epic poetry rose to the height of its achievement almost at its beginning. Hailed as the greatest monument of Persian language and one of the major world epics, it consists of some fifty thousand couplets relating the history of the Iranian nation in myth, legend, and fact, from the beginning of the world to the fall of the Sassanian Empire. Ferdowsi, who belonged to the landed gentry (dehqan) and was well versed in Iranian cultural heritage and lore, fully understood the sense and direction of the work he was versifying. His approximately thirty years of labor produced a magnificent epic of tremendous impact.

A new height in Persian lyric poetry is reached in the thirteenth century with Sadi, a versatile poet and writer of rare passion and eloquence. He holds a position in Persian literature, in terms of the power of expression and the depth and breadth of his sensibilities, comparable to that of Shakespeare in English letters. His sparkling ghazals display a youthful love of life and passion for beauty, be it natural, human, or divine. Sadi's dexterous use of rhetorical devices is often disguised by the beguiling ease of his locution and the effortless flow of his style; his masterly language has been a model of elegant and graceful writing.

The culmination of Persian lyric poetry was reached about a hundred years after Sadi with Hafez, the most delicate and most popular of Persian poets. His ghazals are typical in their content and motifs but exceptional in their combination of noble sentiments, powerful expression elegance of diction and felicity of imagery. His world-view encompasses many Gnostic, mystical, and stoic sentiments, which were the common cultural heritage of his age. While Hafez's satirical lines against pretense and hypocrisy lend a biting edge to his lyrics, his philosophical outlook and Gnostic longings impart an exalted air of wisdom and detachment to his poems. But he is above all a poet of love who celebrates in his ghazals the glory of human beauty and the passion of love. Belief in a mystical "inner meaning" of Hafez's poetry represents the application of a bateni, or esoteric principle, which distorts his meaning and flies in the face of his poetic sense. Hafez is the most notable satirist Persia has produced. Poignant gibes at the hypocritical, judges, professional Sufis, and other pretenders to virtue form an integral part of his ghazals and (following his model) are a common theme of Persian lyrics. The liberal Hafez strongly felt the sting of pretense and cant; to express his outrage was as much a motive for his writing as were his aesthetic and amorous sentiments. But his subtle wit and his magnanimity keep his lyrics from being bitter. Siding with sinners and tavern dwellers, championing the Fends and the kharabatis - the "hippies" of his time - are essentially his protests against the narrow views and bigotry of the establishment, and part of his satirical thrust. To read mystical meanings into all this is to miss the intent and the sense of Hafez's poetry to the detriment of his real worth.

Modernist poetry, namely, a poetry which departs radically from the traditional school of the old masters, began to emerge only after World War II, when the deep social changes which had been developing for some time finally challenged the venerable literary tradition in a drastic fashion and eroded its foundations. It not only dispensed with the necessity of rhyme and consistent meter, but it also rejected the imagery of traditional poetry and departed noticeably from its mode of expression.

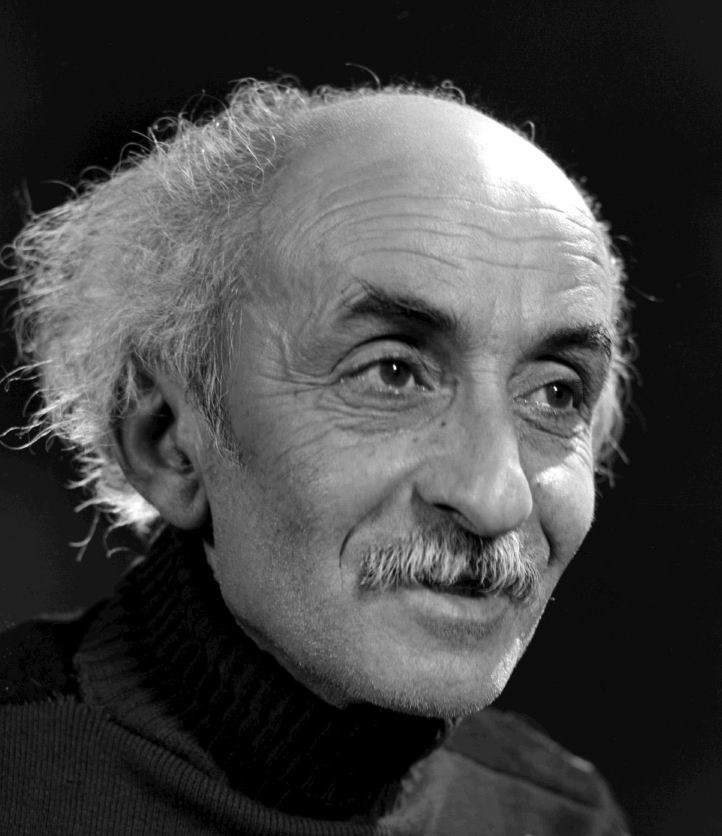

Nima Yushij (1897-1960), the father of modernist poetry, died in relative obscurity, but after World War II a number of young poets took up his cause, fighting against the shackles of literary conventions and writing free verse, sometimes with a vengeance. The vogue gathered momentum, and by the late 1950s it had become the dominant mode of avant-garde Persian poetry. Most of the contemporary literary movements in the West, from the Symbolist to Imagist schools, have found exponents among modernist Persian poets.

In modernist poetry, all formal canons, thematic and imagistic conventions, as well as mystical dimensions of the traditional school are by and large abandoned, and the poets feel free to adapt the form of their poems to the requirements of their individual tastes and artistic outlooks. Hence the great variety of styles among modernist poets. Akhavan-e Thaleth, also a follower of the Nima school, has produced among others, long poems of veiled protest and of epic quality. In Sepehri, a poet of serene simplicity but overweening imagery, we find an original poet singing in praise of the simple pleasures of life and basking in the contemplation of nature.

Iranian Calendar

Iranian official calendar, regulate according to Solar year & Iranian months.21 March, equal 1 Farvardin, is beginning of Iranian New Year. Also in Iran, Lunar calendar announce officially. Lunar year is 10 days less than Solar year ,so days of performing religious rites, that adjust according Lunar calendar, each year is different from next & former years. Therefore it recommended to tourists that arrange their proper traveling time with related agency. Especially in Ramadan month that Muslim Iranian, are fasting and in Muharram are mournful, so these situations influence on daily & current activities and some days in these two month is public holiday. Friday is official holiday.

Currency in Iran

The currency in Iran, or the money used, is called the rial (pronounced reeyaal). The rial is like the dollar or a pound in that is made up of 100 pieces, in Iran called dinars. However, due to high inflation one riyal is worth so little that no fraction of it is really used on a day to day basis. The rial was first introduced as the currency in Iran in 1798 as a coin. Back then it was worth 1250 dinars. Then in 1825 the rial ceased to be issued. The kran of 1000 dinars was then issued as part of a decimal system. The rial replaced the kran at par in 1932, although it was divided into one hundred (new) dinars.

When talking money in Iran you may hear the term toman. The toman is an old term but is no longer an official currency. However it is is still used on a daily basis in Iran and it refers to the amount of ten rials. In Tehran banks are open from 07:30 to 15:30 Saturday to Wednesday and 07:30 to 13:30 Thursday. Friday is a public holiday.

In other cities banks are open from 07:30 to 13:30 Saturday to Wednesday and 07:30 to 12:30 Thursday. Friday is a public holiday. Only selected shops accept MasterCard and Visa credit cards.

https://www.visitiran.ir/currency-iran-1

Post & Means of Mass Communication

Almost, Iran postal system extent to remotest regions of country and each traveler can comminute with farthest world regions by post, telegraph, phone, mobile phone, fax & internet. Various kinds of newspapers in native languages, Persian, Arabic, English & other languages are published daily. Different magazines are published weekly, monthly & annually and various books are published continuously that their information are accessible through computer information bank. Different local, national & international Radio & TV stations always broadcast & telecast programs, in different native languages, Persian & English and other languages daily or sometimes overnight.

People

Iran is a diverse country consisting of people of many religions and ethnic backgrounds cemented by the Persian culture. The majority of the population speaks the Persian language, which is also the official language of the country, as well as other Iranian languages or dialects. Turkic languages and dialects, most importantly Azeri language, are spoken in different areas in Iran. Additionally, Arabic is spoken in the southwestern parts of the country. Religion in Iran is dominated by the Twelver Shi'a branch of Islam, which is the official state religion and to which about 90% to 95% of Iranians belong. About 4% to 8% of Iranians belong to the Sunni branch of Islam, mainly Kurds and Iran's Balochi Sunni. The remaining 2% are non-Muslim religious minorities, including Zoroastrians, Jews, and Christians.

Culture

The Culture of Iran is a mix of ancient pre-Islamic culture and Islamic culture. Iranian culture has long been a predominant culture of the Middle East and Central Asia, with Persian considered the language of intellectuals during much of the 2nd millennium, and the language of religion and the populace before that. The Sassanid era was an important and influential historical period in Iran as Iranian culture influenced China, India and Roman civilization considerably, and so influenced as far as Western Europe and Africa. This influence played a prominent role in the formation of both Asiatic and European medieval art. This influence carried forward to the Islamic world. Much of what later became known as Islamic learning, such as philology, literature, jurisprudence, philosophy, medicine, architecture and the sciences were based on some of the practices taken from the Sassanid Persians to the broader Muslim world. The Iranian New Year (Nowruz) is an ancient tradition celebrated on 21 March to mark the beginning of spring in Iran. It is also celebrated in Afghanistan, Republic of Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan and previously also in Georgia and Armenia. It is also celebrated by the Iraqi and Anatolian Kurds. Nowruz was registered on the list of Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity and described as the Persian New Year by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in 2009.

Historical PeriodsThe First inhabitants of Iran were a race of people living in western Asia. When the Aryans arrived, they gradually started mingling with the old native Asians. Aryans were a branch of the people today known as the Indo-Europeans, and are believed to be the ancestors of the people of present India, Iran, and most of Western Europe.

Recent discoveries indicate that, centuries before the rise of earliest civilizations in Mesopotamia, Iran was inhabited by human. But the written history of Iran dates back to 3200 BC. It begins with the early Achaemenids, The dynasty whose under the first Iranian world empire blossomed.

Cyrus the Great was the founder of the empire and he is the first to establish the charter of human rights. In this period Iran stretched from the Aegean coast of Asia Minor to Afghanistan, as well as south to Egypt. The Achaeamenid Empire was overthrown by Alexander the Great in 330 BC and was followed by The Seleucid Greek Dynasty.

After the Seleucids, we witness about dozen successive dynasties reigning over the country, Dynasties such as Parthian, Sassanid, Samanid, Ghaznavid, Safavid, Zand, Afsharid, Qajar and Pahlavi. In 641 Arabs conquered Iran and launched a new vicissitudinous era. Persians, who were the followers of Zoroaster, gradually turned to Islam and it was in Safavid period when Shiite Islam became the official religion of Iran.

Since Qajar dynasty on, due to the inefficiency of the rulers, Iran intensely begins to decline and gets smaller and smaller. The growing corruption of the Qajar monarchy led to a constitutional revolution in 1905-1906. The Constitutional Revolution marked the end of the medieval period in Iran, but the constitution remained a dead letter.

During World Wars I and II the occupation of Iran by Russian, British, and Ottoman troops was a blow from which the government never effectively recovered.

In 1979, the nation, under the leadership of Great Imam Khomeini, erupted into revolution and the current Islamic republic of Iran was founded.

Handicrafts

Recent archaeological excavations have shed new light on the earliest arts of the Iranian plateau. These newly discovered prehistoric sites date back to at least 5000 BC, and handsome decorated pottery, some of which is eggshell thin, has been found in great quantities at sites dated 3000 BC and later. Persian art and architecture reflects a 5,000-year-old cultural tradition shaped by the diverse cultures that have flourished on the vast Iranian plateau occupied by modern Iran and Afghanistan. The history of Persian art can be divided into two distinct eras whose demarcation is the mid-7th century AD, when invading Arab armies brought about the conversion of the Persian people to Islam.

https://www.mcth.ir/english/Handicrafts

Traditional Food

Cuisine of Iran is of a wide variety and the culinary of Iran reflects the tradition of the country and the region in a great way. Cuisine of Iran comprises of both cooked and raw foods. The cooked foods are mostly non-vegetarian and the raw foods comprises of fruits and nuts, herbs and vegetables. Cuisine of Iran speaks of the wide variety of appetizers and desserts that is more famous all over the world.

Cuisine of Iran goes bland without the spices used in a special way in most of the dishes. Some of the major dishes that Cuisines of Iran extensively and importantly consists of are the rice, bread. There are varieties of rice preparation, the preparation differs with region and course of the

meal. Chelow, Damy, Pollo and Kateh are the most common rice preparation famous in Iran. The bread are referred to as Nan. Iranian Cuisines also stands famous because of the wide range of drink that they make from several fruits. The traditional drink that Iranian people have with the mea

l is known as Doogh. Sharbat and Khak sheer are the types of drink that is popular and famous in Iran.

https://www.visitiran.ir/type/cuisine

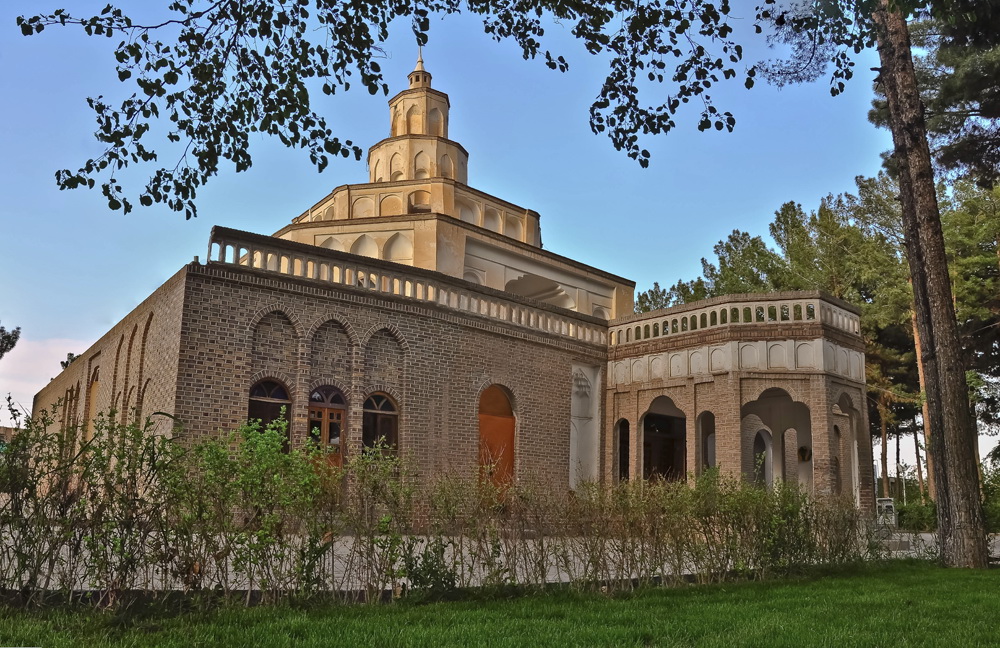

Architecture

Building first evolved out of the dynamics between needs (shelter, security, worship, etc.) and means (available building materials and attendant skills). As human cultures developed and knowledge began to be formalized through oral traditions and practices, building became a craft, and "architecture" is the name given to the most highly formalized and respected versions of that craft. Architecture is integrate part of history, economy, social issue, culture and tradition of each society.

The architecture in Iran dates back to 5000 BCE to the present with characteristic examples distributed over a vast area from Syria to North India and the borders of China, from the Caucasus to Zanzibar. Persian buildings vary from peasant huts to tea houses, and garden pavilions to "some of the most majestic structures the world has ever seen.

Most important properties of traditional Architecture of Iran include: harmony with the nature and environment and take benefit from natural facilities of the location, harmony with the traditions of all provinces, Iranian architecture portray detail of life, beliefs, moral, ethic code and some other. The essence of traditional Architecture of Iran consists of math and theosophy. As, in ancient Iranian books architecture is named as alhaseb and almohandess.

Motif of Iranian architecture has been its cosmic symbolism "by which man is brought into communication and participation with the powers of heaven". This theme, shared by virtually all Asia and persisting even into modern times, not only has given unity and continuity to the architecture of Persia, but has been a primary source of its emotional characters as well.

The traditional architecture of the Iranian lands throughout the ages can be categorized into the six following classes or styles:

Pre-Islamic: The Parsian style (Achaemenid, Median, Elamite eras), The Parthian style (Parthian, Sassanid eras).

Islamic: The Khorasani style, The Razi style, The Azari style, The Isfahani style

Available building materials dictate major forms in traditional Iranian architecture. Heavy clays, readily available at various places throughout the plateau, have encouraged the development of the most primitive of all building techniques, molded mud, compressed as solidly as possible, and allowed to dry. This technique used in Iran from ancient times has never been completely abandoned. The abundance of heavy plastic earth, in conjunction with a tenacious lime mortar, also facilitated the development of the brick.

Iranian architecture take advantage of abundant symbolic geometry, using pure forms such as the circle and square, and plans are based on often symmetrical layouts featuring rectangular courtyards and halls. All traditional Persian houses have following sections: Hashti and Dalan-e-vorudi. Entering the doorway one steps into a small enclosed transitional space called Hashti. Here one is forced to redirect ones steps away from the street and into the hallway, called Dalan e Vorudi. In mosques, the Hashti enables the architect to turn the steps of the believer to the correct orientation for prayer hence giving the opportunity to purify oneself before entering the mosque. A central pool with surrounding gardens Important partitionings such as the biruni (exterior) and the andaruni (interior). Persian houses in central Iran were designed to make use of an ingenious system of wind tower that create unusually cool temperatures in the lower levels of the building. Thick massive walls were designed to keep the suns heat out in the summertime while retaining the internal heat in the winters.

Famous Architectural Sites in Iran are; Meidan-e-Emam, Takht-e-Soleyman, Bisotun, Persepolis, Pasargadae, Bam, Ifahsan, Soltaniyeh, Tchogha Zabnil. .Iran also enjoys sme number of world known villages that has unique architectural feature like Abyaneh in the central part of Iran and Masouleh in the northern part of the country in both of villages it is the nature who is architecture.

Persian Gardens

The tradition and style in the garden design of Persian gardens has influenced the design of gardens from Andalusia to India and beyond. The gardens of the Alhambra show the influence of Persian Paradise garden philosophy and style in a Moorish Palace scale from the era of Al-Andalus in Spain. The Taj Mahal is one of the largest Persian Garden interpretations in the world, from the era of the Mughal Empire in India.

https://www.visitiran.ir/attraction/persian-gardens

Music

About the music of the Elamites not much is known; however, we know of a ruler of Susa who had musician at his temple gate about 2600 BC. There are also the bas-relief which shows musicians playing harps and tambourine. It is possible that there was not a lot of difference between Babylonian-Assyrian music and Iran at that time and the Persian names of tabire (drum) and karranay (trumpet) may be derived from names of the Akkadian tabbalu and qarnu.

After the conquest of Alexander the Great when Hellenistic culture found expression in Persia, one might suppose that Greek derived the name of salpinx (trumpet) from Iranians. During Parthian period ( beginning 2nd century BC) when Aramaic became the official language, the word shaipur (trumpet) which is Semitic may be taken from Aramaic word.

Sassanian dynasty cherished music as shown on rock carvings of Taq-i Bustan which are two types of harp, trumpet and drums. Also, lute (ud), guitar (rubab) and pandore (tanbura) can be seen from other arts. We also know that specific modes of music were used at certain hours of the day, week, and month, each for a particular purpose as a part of governmental procedure.

After entering Islam into Iran, Arabic music became known in Iran. At the same time, Persian music influenced Arabic music. In the 10th century, Persian musicians became favorite at Arab court and the Persian lute was a favored instrument.

In the 9th century, the Khorasanian scale was introduced. The musicians played on Persian tanbur which became as popular as lute. The nay (flute), chang (harp), rabab (viol), and the nay-i siyah (reedpipe) were also common instruments at the time.

Persian theorists were leaders in Arabian musical theory, for example, Al-Razi and Al-Sarakhsi. Ibn Sina mentions twelve principal modes of music:Rahawi, Husain, Rast, Busalik, Zangula, Ushshaq, Hijaz, Iraq, Ispahan, Nava, Buzurg, and Mukhalif (zirafgand). We know little about their formation. Four of modes mentioned above have Arabic names which may indicate Arabian origin. Ispahan was named as one of the ancient modes of Persia. There are also six secondary modes (avazat).

During Ghuri rulers and Khwarizmi (12th -13 th century) music grew. Two notable theorists of this era were Fakhr al-Din al Razi and nasir al-Din al Tusi. Another Persian theorist was Qutb al Din al-Shirazi who was famous for Pearl of Crown (Durrat al-taj). In the Treasure-House of Gift (Kanz al -Tahaf) an important work in 1350, ud (lute), rubab (guitar), mughni ( archlute), chang (harp), nuzha, qanun (psaltery),

ghishak (spiked viol), pisha (fife) and nay-i siyah (reedpipe) are completely described. In other places, dutar (two strings) and sitar (three strings) exquisite of poet Hafez are mentioned.

During Timuri Dynasty, Abdal-Qadir ibn Ghaibi lived who wrote The compiler of Melodies (Jami al-alhan) which is cherished in the Bodleian Library at Oxford. By the 14th and 15th century, twenty four branch modes (shuba) and forty eight derived modes (gusha) began, respectively. By the 17th century, there were twenty four of rhythmic modes (usul).

Under Safavid Dynasty, chartar (four strings) and sheshtar (six strings) musical instruments were invented. Ud (lute) and kamancha (spiked viol) were the most favorite instruments with addition of nay (flute) and daira (tambourine) as can be seen in a painting of Shah Safi court. Surnay (shawm), naqqarat (kettledrums), karna (long trumpet), duhul (side drum), and kus (kettledrum) were for military uses. Persian theory especially in nomenclature influenced Indian, Arabian, Turkish and Turkomanian music. Even China through Turkomans was affected by Persian instruments.

By the 19th century, ud (lute), rubab (guitar), qanun (psaltery) were not in use but santur (dulcimer) was still used. During the second half of the 19th century, three viols rumuz, madilan, and tarab angiz were introduced.

About the mid century, European influence found its way into Persia, mostly in military bands. In the early 20th century, Ali Naqi khan Vaziri a teacher, a composer and instrumentalist played an important role in reviving and advancing the native music of Persia. Vaziri gives the notation of most popular modes (avaz); Mahur, humayun, Bayat-i Ispahan, chahargah, shur, segah, nava, and bayat-i kurd. Pish dar amad is an introduction which prepares the listener for dastgah (melodic modes) which are the pieces to come.

Cultural Diversity

Iran is a culturally diverse society, and inter-ethnic relations are generally harmonious. The predominant ethnic and cultural group in the country consists of native speakers of Persian. But the people who are generally known as Persians are of mixed ancestry, and the country has important Turkic and Arab elements in addition to the Kurds, Baloch, Bakhtyari, Lurs, and other smaller minorities (Armenians, Assyrians, Jews, and others).

The Persians, Kurds, and speakers of other Indo-European languages in Iran are descendants of the Aryan tribes that began migrating from Central Asia into what is now Iran in the 2nd millennium B.C. Those of Torkish ancestry are the descendants of tribes that appeared in the region also from Central Asia beginning in the 11th century ad, and the Arab minority settled predominantly in the countrys southwest, in Khuzestan. The Kurds have been both urban and rural (with a significant portion of the latter at times nomadic), and they are concentrated in the western mountains of Iran. Closely related are the Bakhtyari tribes, who live in the Zagros Mountains west of E?fahan.

The Baloch are a smaller minority who inhabit Iranian Baluchistan, which borders on Pakistan. The larges group is the Azerbaijanians, a farming and herding people who inhabit two border provinces in the northwestern corner of Iran. Two other Turkic ethnic groups are the Qashqai, in the Shiraz area to the north of the Persian Gulf, and the Turkmen, of Khorasan in the northeast.

The Armenians, with a different ethnic heritage, are concentrated in Tehran, E?fahan, and the Azerbaijan region and are engaged primarily in commercial pursuits. A few isolated groups speaking Dravidian dialects are found in the Sistan region to the southeast. Jews, Assyrians, and Arabs, constitute only a small percentage of the population.

Theater and Cinema

The most popular form of entertainment in Iran is the cinema. Cinema is also an important medium for social commentary. Iran's film industry became one of the finest in the world, with festivals of Iranian films being held annually throughout the world. Fajr Film Festival is arranged annually in Tehran and has gained international recognition in recent years. Iranian and foreign films are screened and are awarded.

The nearest thing to the theater in Iran used to be the religious re-enactment of holy stories, known as tazie, but theater in European style was introduced to Iran only in the second decade of the 20th century. Initial work was concentrated in Tehran and Rasht. The quick advent of cinema and, later, television in Iran soon after the introduction of theater left little initial opportunity for the latters development.

The first cinema hall was constructed in Tehran in the late 1920's. However, foreign films were the only source for cinemas, and these were shown with sub-titles. Dubbing into the Persian began in 1948, while serious shooting of Iranian films did not begin until 1950. Iranian Young Cinema society was founded in 1974 and its statute officially was approved by the then Supreme Consultative of Culture & Art in 1975. But it was after the Islamic Revolution of Iran that the society started its activities with new policies and aims in 1985 which as follows, to flourish the creativities and talents of the enthusiastic youths who are interested in film making and photography, to train the enthusiastic youths in order to improve their cine culture, to conduct the processes of film making, and amateur photography in Iran.

In the beginning, Iranian Young Cinema Society mainly focused its activities on producing 8 & 16 mm films through establishing training courses, thereafter, holding regional and annual festivals were also taken into Consideration in the frame of its programs. The society started its activities along with its four offices in Tehran and at the present time the society has established fifty branches throughout the country.

Visa

Entry visa (single, double, multiple entry, work permit, tourist or pilgrimage) applies to foreign nationals who wish to travel to Iran on official business, trade negotiations, participation in seminars/conferences (economic, cultural etc), work related issues, for sports activities, tourism or pilgrimage.

https://www.visitiran.ir/visa

Transportation

Air: Many international visitors to Iran arrive by air, with IKA International Airport in Tehran having excellent worldwide connections including to destinations such as London, Paris, Milan, Amsterdam, Berlin, Stockholm, Moscow, Istanbul, Dubai, Beijing, Seoul, Bangkok and New Delhi. Airline companies operating flights to IKA International Airport include: Lufthansa, Alitalia, Turkish Airlines, KLM, Emirates, Etihad and British Airways as well as domestic airlines such as Iran Air, Mahan Air and Caspian Airlines.

Facilities at the airport include outlets for dining and refreshments, basic passenger services and limited transport options for getting into the city. Arriving passengers can choose from taking a taxi or a bus into the city, or alternatively, those with pre-booked accommodation can arrange to be met by a hotel representative. In addition to the airport at Tehran, the following Iranian airports offer some limited international flights: Mashhad International Airport (Mashhad), Shiraz International Airport (Shiraz), Bandar Abbas International Airport (Bandar Abbas), Esfahan International Airport (Esfahan), Tabriz International Airport (Tabriz) and Zahedan International Airport (Zahedan).

Car: Iran can be reached by car from various neighbouring countries, although drivers are encouraged to research their journey well in advance. Visitors are not advised to travel overland to Iran from Pakistan and anyone who must travel in this area should exercise extreme caution. We advise that you only travel on main roads and avoid travelling at night if you intending on reaching Iran by car via an international border. The border areas with Afghanistan and Iraq are considered insecure and visitors are strongly advised to avoid travel in these areas. The border with Turkey is frequently used by visitors wanting to access Iran by road.

Rail: Two international train routes are available to Iran; one is from Istanbul to Tehran, with a once weekly departure (72 hours) and the other is from Damascus to Tehran, again a once weekly departure (64 hours). Journeys are long, but prices are reasonable and most overnight services offer sleeping cars that have a capacity for four people.

Sea: Although it is possible to arrive in Iran by using a sea route across the Persian Gulf, this method of arrival is rarely used nowadays, with air travel being considered much more convenient.

Bus: Travelling by bus from Turkey to Iran is feasible, although journey times can be very lengthy. Prices of bus tickets are cheap and there are various levels of comfort available, with first class coaches offering reclining seats, air conditioning and free water.

Accommodations

Iran has a reasonable choice of accommodation, from tiny cells in noisy guest house to luxury rooms in world-class hotels. Hotels are available in most towns and they are classified according to the star system. During the summer months and Nowruz, prices tend to be higher and hotels are busier. A guest house can offer anything from a bed in a noisy, grotty, male-only dorm to a small, simple, private clean room. However they are the best option for those on the tightest budgets. Along the Caspian Sea coast and in rural resort-villages you can find local, renting out rooms in their homes. Such options include "suits", which are furnished, self-contained apartments or bungalows. Villas are also popular there.

Iran's Attractions

Iran is one of the few countries that have all four distinguished seasons. And at any time of the year, in each section of the country, one of the four seasons is visible. Iran's variety in terms of temperature, humidity and rainfall differs from place to place and season to season. Length of the seasons differs in different regions.

Natural Regions

As one of the world's most mountainous countries, Iran contains two major ranges of mountains, the Alborz with the highest peak in Asia west of the Himalayas, Damavand (5671 m above sea level) and the Zagros that cuts across the country for more than 1,600 km extending from north west to the south east of the country. The peaks exceeding 2,300 m in these two ranges capture a considerable amount of moisture coming either from the Caspian Sea southward or the Mediterranean eastward.

Deserts of Iran: Iran is situated in a high-altitude plateau surrounded by connected ranges of mountains. The well-known deserts of Iran are at two major regions: Dasht-e-Kavir, and Kavir-e-Lut. They are both some of the most arid and maybe hottest areas of their kinds in the world.

The Desert Pits of Iran: Kavir-e-Lut is the largest pit inside the Iranian plateau and probably one of the largest ones in the world. Kavir-e-Lut is a pit formed by broken layers of the earth.

Mountains of Iran: The whole area of Iran can be divided in to four parts: 1/2 mountains as one part, and 1/4 deserts and 1/4 fertile plains as the other part. There are two major ranges of mountains called the Alborz and the Zagros.

- The Alborz have been extended all the way from Azerbaijan to Afghanistan passing through the southern part of the Caspian Sea.

- The Zagros have covered a region from Azerbaijan to the west and SE of the country.

- The highest peak of Iran (Middle East) called "Damavand", 5671m ASL. It is a burned-out volcano with a crater of 400m width. At times, sulfur gas ascends to the top and covers the peak like clouds.

Rivers of Iran: There is a vastly extended network of rivers in Iran most of which seasonally are filled with water. Some permanent rivers run from the Alborz or the Zagros to the Caspian Sea, Persian Gulf and Oman Sea. Some temporary rivers either run into a body of water or get dried before reaching any watershed.

Sea, Gulf & Lakes of Iran: Persian Gulf is situated at the south of Iran. It is almost 900km long from the Strait of Hormoz to Arvand Rud, the border river between Iran and Iraq. The Persian Gulf is one of the warmest bodies of water in the entire Middle East.

Oman Sea, situated at the south of Iran, connects the Persian Gulf to the Indian Ocean. With an approximate area of 903,000 km, the Oman Sea is surrounded by Iran and Pakistan at the north, Deccan peninsula at the east and Arabia peninsula at the west.

Iran has got small ports at its shorelines with the Oman Sea like Chabahar, Gavater and Jask.

Since antiquity, the Strait of Hormoz and the Oman Sea have always been strategic waterways. Today, tens of gigantic oil tankers carry oil every day from the countries in the region through this route to different parts of the world.

With an area of approximately 371,000sq.km, Caspian Sea in the largest body of inland water all over the world, which is situated at the north of Iran. Its neighboring countries are Iran at the South, Turkmenistan at the SE, Kazakhstan at the NE and north, Russia at the NW and Azerbaijan at the SW.

The Iranian shorelines are approximately 992km from the East to the West. The average level of of the Caspian Sea is 28m below sea level. There are geographic areas born at the Iranian shorelines because of the changes in the level of the sea, like Miankaleh Peninsula, Ashuradeh IslandHossein Qolly Bay, Gorgan Bay and Anzaly Bay.

Religions

Christians, Jews, and Zoroastrians are the most significant religious minorities. Christians are the largest group, Orthodox Armenians constituting the bulk. The Assyrians are Nestorian, Protestant, and Roman Catholic, as are a few converts from other ethnic groups. The Zoroastrians are largely concentrated in Yazd in central Iran, Kerman in the southeast, and Tehran. These religious minorities are spread all over the country; they practice their own rituals and add to the beauty of this country living in peace and harmony with the Islamic majority. All these different religious groups have permanent representatives in House of Parliament.

Virtual Arts

Although in the West the term Persian culture is commonly used, the inhabitants of this country have long called it Iran and themselves Iranians, rather than Persians. In accordance with popular usage, however, the term Persian will be used in this article to refer to the period before the advent of Islam in the 7th century ad, that is, the period of the ancient Persian empires as well as to prehistoric times. Ceramics and clay figurines were the chief artworks of the prehistoric period, and architecture and sculpture predominated during the period of the first two Persian empires (6th century bc to 7th century ad). After introduction of Islam in the 7th century ad, sculpture was little practiced but architecture flourished. Painting became a major art in the period from the 13th to the 17th century. In the 20th century these ancient arts were being revived, and traditional forms were combined with Western technology and contemporary materials.

After the conquest of Persia by Alexander the Great in 331 bc, and the assumption of power by the Seleucid dynasty, Persian architecture followed the styles common to the Greek world. Subsequently, under the Parthian Arsacid dynasty, which lasted from about 250 bc to ad 226, a small number of buildings was constructed in native Persian style. The most notable monument of this period is a palace at Hatra (now al-Hadhr, Iraq), dating from the 1st or 2d century ad and exemplifying the use of the barrel vault on a grand scale. The vaults, heavy walls, and small rooms of this palace indicate a continuation of earlier Assyrian and Babylonian tradition. A great renaissance in architecture took place under the Sassanid dynasty, which ruled Persia from 226 until the Islamic conquest in 641.

Other major structures include the mausoleums of the Mongol conqueror Tamerlane and his family at Samarqand, the Royal Mosque at Meshad-i-Murghab, and the vast madrasahs, or mosque schools, at Samarqand, all of which were erected during the 15th century. Under the Safavid dynasty (1502- 1736), a vast number of mosques, palaces, tombs, and other structures were built. Common features in the mosques were onion-shaped domes on drums, barrel-vaulted porches, and pairs of towering minarets. A striking decoration was the corbel, a projection of stone or wood from the face of a wall, used in rows and tiers. These corbels, arranged to appear as series of intersecting miniature arches, are usually called stalactite corbels. Color was an important part of the architecture of this period, and the surfaces of the buildings were covered with ceramic tiles in glowing blue, green, yellow, and red. The most notable Safavid buildings were constructed at Esfahan, the capital at that period. The city, laid out in broad avenues, gardens, and canals, contained palaces, mosques, baths, bazaars, and caravansaries.

Since the 18th century, the architectural styles of western Europe have been adopted to an increasing degree in Iran. At the same time, traditional forms have remained vital, and native and imported elements have often been combined in the same building. Recently, unadorned steel and concrete structures, similar to those seen in other parts of the modern world, have been built as dwellings, public buildings, and factories.

Bisotun Inscriptions

Theprimary scientific studies regarding the engravements and inscriptions of Bisotun were made in 1835, by Henry Rawlinson, a young British officer. After which this research was carried on by several scientists who added their discoveries to this historical treasure. The text of this inscription was engraved in the breast of the mountain in 522 BC. by a decree from Dariush. The same relates to the war which lasted for two and a half years, between him and his opponents in order to gain power. Encircling the Bistoon impression is an epigraph in three languages, named as, the ancient Parsi, Elamite and a Babylonian dialect. The Elamite text is to the right of the impression, the second to the left, running parallel to the Parsi text. Whereas, the Babylonian text stands above that of the second Elamite inscription. Additional and complete translations can be observed in the surroundings and to the right.

The ancient Parsi text is in 414 lines and engraved in a beautiful uniform script on a polished surface. In all the epigraphs of Dariush the Achaemenian begins with the phrase "King Dariush proclaims" and this is repeated throughout his decrees, emphasizing the grandeur and greatness of the power of this monarch. This sovereign owned his victory to Ahura Mazda and thus offered a religious effect to the epigraph to a great extent. This view can be noted and brought to light specially in the fourth column of the inscription.

Nagsh-e Rostam

Nagshe-Rostam is located about 6km north of Persepolis. Hewn out of the rock on the mountain face are the tombs of the Achamenid kings Darius I, Artaxerxes, Xerxes I and Darius II. Below them are huge Sassanian bas reliefs (224-637 AD). Pasargadae is the site of the tomb of Cyrus the Great founder of the Persian Empire, a huge square mausoleum twelve metres high.

In the same direction as the historical site of Nagsh-e-Rajab and at the termination of the Haji-Abad Mountain, there are many historical ruins belonging to the Achaemanian, Elamite and Sassanian periods. These sites include: The stone carvings on the lower slopes (Sassanian), tombs of the Achaemanian Kings on the top of the hill and the square-shaped monument (Zoroastrian inscription) on the right side. This complex no doubt is a major tourist attraction site specially for those interested in archaeology and history. Details of the carvings :

The impression shows Nerssi (296-304 AD), the elder son of Shapour I as being designated the King by Anahita (Nahid).

This carving is located at the lower portion of the tomb of Darius the Great and consists of two similar seats. The upper image shows Bahram II (277-293 AD) fighting the enemy. Representing the conquest of Shapour I (242-271 AD) against Valerian the Roman Emperor. In this carving Shapour I is sitting on a horse and Valerian kneeling by the horse. Ceriyadis (the challenger of Valerian) is standing in front of the horse, and the king of Iran with streched hands, offers him a ring, to rule east roma country. This carving shows the conquest of Hormozd II, the Sassanian Monarch. A picture of Bahram II defeating the enemy. This famous carving is of great importance. It shows a person who is standing. To his left, a head and face can be seen. A representation of Ardeshir Babakan (226-242 AD), this carving shows him being designated as the King by Ahura Mazda.

https://www.visitiran.ir/attraction/naqsh-e-rostam

Shapour Stone Carving

Ithasremained as a part of a thriving city. The ruins of Shapour exists in the Chogan Valley, a few kilometers away from Kazeroon. In the Chogan Valley, on the precipice of the mountain and on both sides of a river, many carvings can be distinguished: Two men on their horses standing face to face and a third person bending on his knees stretching his hands as though begging for forgiveness.

It seems to be an impression of Shapour on a horse, with curly hair and a crown of a monarch. Above Shapour's head there is an angel with a horn. On two sides of the carvings, are two arches, in each of which three people are encarved. It seems that Shapour is apparently receiving people with gifts for him. This shows Shapour with two armed soldiers on their horses, one of them is giving a ring to the other.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

International Registered Monuments

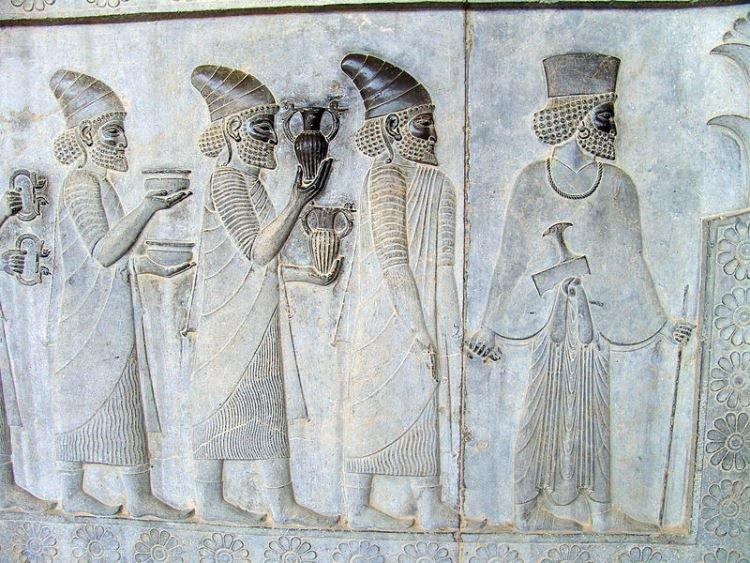

Perspolis

Founded by Darius I in 518 B.C., Persepolis was the capital of the Achaemenid Empire. It was built on an immense half-artificial, half-natural terrace, where the king of kings created an impressive palace complex inspired by Mesopotamian models. The magnificent ruins of Persepolis lie at the foot of Kuh-i-Rahmat (Mountain of Mercy) in the plain of Marv Dasht about 650 km south of the present capital city of Teheran. Founded by Darius I in 518 BC (although more than a century passed before it was finally completed by Artaxerxes I), Persepolis was the capital of the Achaemenid Empire. An inscription carved on the southern face of the terrace proves that Darius the Great was the founder of Persepolis. It was built on an immense half-artificial, half-natural terrace, where the King of Kings created an impressive palace complex inspired by Mesopotamian models. Before any of the buildings could be erected, considerable work had to be done: this mainly involved cutting into an irregular and rocky mountainside in order to shape and raise the large platform and to fill the gaps and depressions with rubble. The terrace of Persepolis, with its double flight of access stairs, its walls covered by sculpted friezes at various levels, contingent Assyrianesque propylaea, the gigantic winged bulls, and the remains of large halls, is a grandiose architectural creation.

The studied lightening of the roofing and the use of wooden lintels allowed the Achaemenid architects to use, in open areas, a minimum number of astonishingly slender columns. They are surmounted by typical capitals where, resting on double volutes, the forequarters of two kneeling bulls, placed back-to-back, extend their coupled necks and their twin heads, directly under the intersections of the beams of the ceiling, Persepolis was the example par excellence of the dynastic city, the symbol of the Achaemenid dynasty, which is why it was burned by the Greeks of Alexander the Great in 330. According to Plutarch, they carried away its treasures on 20,000 mules and 5,000 camels. What remains today, dominating the city, is the immense stone terrace (530 m by 330 m), half natural, half artificial, backed against the mountains. It seems that Darius planned this impressive complex of palaces not only as the seat of government but also, and primarily, as a show place and a spectacular centre for the receptions and festivals of the Achaemenid kings and their empire. Darius lived long enough to see only a small part of his plans executed. This ensemble of majestic approaches, monumental stairways, throne rooms (Apadana), reception rooms and annex buildings is classified among the world's greatest archaeological sites, among those which have no equivalent and which bear witness of a unique quality to a most ancient civilization. During the following centuries many people travelled to and described Persepolis and the ruins of its Achaemenid palaces. The ruins were not excavated until the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago sponsored an archaeological expedition to Persepolis and its environs under the supervision of Ernst Herzfeld from 1931 to 1934, and Erich F. Schmidt from 1934 to 1939.

On a terrace, as if on a pedestal, the Achaemid kings, Darius (522-486 BC), his son Xerxes (486-65 BC) and his grandson Artaxerxes (465-24 BC) built a splendid palatial complex: propylaea, formal halls and private apartments opening in to courts linked by staggered corridors, based on Mesopotamian forerunners. The Persepolis visible today is mostly the work of Xerxes; the northern part of the terrace, consisting mainly of the Audience Hall of the Apadana, the Throne Hall and the Gate of Xerxes, represented the official section of the Persepolis complex, accessible to a restricted public. The other part held the palaces of Darius and Xerxes, the Harem, the Council Hall and such.

As in Mesopotamia, the principal building material was sun-dried brick; yet the ashlar, mainly used for supporting elements (jambs and lintels of doorways, casings, window-breasts, bases and capitals, etc.), for monumental doorways and for vast sculpted surfaces, has happily survived the vicissitudes of time.

https://www.visitiran.ir/attraction/persepolis

Tchogha Zanbil

The ruins of the city of the Kingdom of Elam, surrounded by three huge concentric walls, are found at Tchogha Zanbil. Founded c. 1250 B.C., the city remained unfinished after it was invaded by Ashurbanipal. The current name of Tchogha-Zanbil corresponds with the ancient city of Dur Untash, dominating the course of the Ab-e Diz, a tributary of the Karun. The city was founded as a religious capital during the Elamite period by Untash-Napirisha (1275-1240 BC) in a site half-way between Anshn and Suse. Roman Ghirshman carried out the complete exploration of the site from 1951 to 1962. The site contains the best preserved and the largest of all the ziggurats of Mesopotamia. The first enclosure contains the temenos. In origin, the temple located at the centre was a square building, dedicated to the Sumerian god Inshushinak. This temple was then converted into a ziggurat of which it constitutes the first storey. The solid masses of the four other storeys are in the other XX starting from the ground of the court (and not one on top of the other as in Mesopotamia) so as to cover all the surface of the old central court

Access was by means of a vaulted staircase, invisible from outside, unlike the squatter Mesopotamian ziggurats, which were equipped with three external staircases, Today the ziggurat is no more than 25 m high, the last two stages, which originally rose to a height of 60 m, having been destroyed. The ziggurat is sacred not only to Inshushinak but also to Napirisha, the god of Anshn. On the north-western side of the ziggurat a group of temples were dedicated to the minor divinities, Ishnikarab and Kiririsha. An oval wall surrounded the temples and the ziggurat. The second enclosure, trapezoidal in form, delimits a vast, almost empty zone. In the third enclosure, only three palaces were built and a temple, near the Royal Gate, with a large interior court. This third enclosure was to protect the town of Dur Untash, the houses of which were never built. The Untash-Gal Palace (13th century BC) was discovered, separated from the temenos.

In spite of the destruction attributed to the Assyrians, a whole series of heads, statuettes, animals and amulets were found, and the remains of two panels in ivory mosaic. Several vaulted tombs were discovered in the basement of the royal residence, with evidence of cremation. Nearby was a temple dedicated to Nusku, the god of fire. To supply the population of the city with water, Untash-Napirisha made a channel of about 50 km long, leading to a reservoir outside the northern rampart; from there, nine conduits carried the filtered water to a basin arranged inside the rampart. Dur Untash was given up by the Elamite kings in the 12th century BC in favour of Susa. They transported all the treasures of Tchogha Zanbil to Susa where they were used to decorate the recently restored temples. In 640 BC, Dur Untash was entirely destroyed by the Assyrian king Assurbanipal, a few years after his conquest of Susa.

https://www.visitiran.ir/attraction/tchogha-zanbil

Takht-e Soleyman

The archaeological site of Takht-e Soleyman, in north-western Iran, is situated in a valley set in a volcanic mountain region. The site includes the principal Zoroastrian sanctuary partly rebuilt in the Ilkhanid (Mongol) period (13th century) as well as a temple of the Sasanian. Takht-e Soleyman is an outstanding ensemble of royal architecture, joining the principal architectural elements created by the Sasanians in a harmonious composition inspired by their natural context. The composition and the architectural elements created by the Sasanians at Takht-e Soleyman have had strong influence not only in the development of religious architecture in the Islamic period, but also in other cultures. The ensemble of Takht-e Soleyman is an exceptional testimony of the continuation of cult related to fire and water over a period of some two and half millennia. The archaeological heritage of the site is further enriched by the Sasanian town, which is still to be excavated. Takht-e Soleyman represents an outstanding example of Zoroastrian sanctuary, integrated with Sasanian palatial architecture within a composition, which can be seen as a prototype. As the principal Zoroastrian sanctuary, Takht-e Soleyman is the foremost site associated with one of the early monotheistic religions of the world. The site has many import

ant symbolic relationships, being also a testimony of the association of the ancient beliefs, much earlier than the Zoroastrianism, as well as in its association with significant biblical figures and legends.

Takht-e Soleyman is an outstanding ensemble of royal architecture, joining the principal architectural elements created by the Sassanians in a harmonious composition inspired by their natural context. The composition and the architectural elements created by the Sassanians there have exerted a strong influence not only in the development of religious architecture in the Islamic period, but also in other cultures. The ensemble represents an outstanding example of a Zoroastrian sanctuary, integrated with Sassanian palatial architecture within a composition, which can be seen as a prototype.It is an exceptional testimony of the continuation of a cult related to fire and water over a period of some two-and-a-half millennia. The archaeological heritage of the site is further enriched by the Sassanian town, which is still to be excavated.

Takht-e Soleyman is situated in Azerbaijan province, within a mountainous region, some 750 km from Teheran. It is formed from plain, surrounded by a mountain range and it contains a volcano and an artesian lake as essential elements of the site.The site consists of an oval platform about 350 m by 550 m rising 60 m above the surrounding valley. It has a small calcareous artesian well that has formed a lake some 120 m deep. From here, small streams bring water to surrounding lands. The Sassanians occupied the site starting in the 5th century, building there the royal sanctuary on the platform. The sanctuary was enclosed by a stone wall 13m high, with 38 towers and two entrances (north and south). This wall apparently had mainly symbolic significance as no gate has been discovered. The main buildings are on the north side of the lake, forming an almost square compound (sides c. 180 m) with the Zoroastrian Fire Temple (Azargoshnasb) in the centre. This temple, built from fired bricks, is square in plan. To the east of the Temple there is another square hall reserved for the 'everlasting fire'. Further to the east there is the Anahita temple, also square in plan. The royal residences are situated to the west of the temples.

The lake is an integral part of the composition and was surrounded by a rectangular 'fence'. In the north-west corner of this once fenced area, there is the so-called Western iwan, 'Khosrow gallery', built as a massive brick vault, characteristic of Sassanian architecture. The surfaces were rendered in lime plaster with decorative features in muqarnas (stalactite ceiling decoration) and stucco. The site was destroyed at the end of the Sassanian period, and left to decay. It was revived in the 13th century under the Mongol occupation, and some parts were rebuilt, such as the Zoroastrian fire temple and the Western iwan. New constructions were built around the lake, including two octagonal towers behind the iwandecorated in glazed tiles and ceramics. A new entrance was opened through the main walls, in the southern axis of the complex. It is noted that the surrounding lands in the valley (included in the buffer zone) contain the remains of the Sassanian town, which has not been excavated. A brick kiln dating from the Mongol period has been found 600 m south of Takht-e Soleyman. The mountain to the east was used by the Sassanians as a quarry for building stone.

Zendan-e Soleyman is a hollow, conical mountain, an ancient volcano, some 3 km to the west of Takht-e Soleyman. It rises about 100 m above the surrounding land, and contains an 80 m deep hole, about 65 m in diameter, formerly filled with water. Around the top of the mountain, there are remains of a series of shrines and temples that have been dated to the 1st millennium BCE. The Belqeis Mountain ( c. 3,200 m), is situated 7.5 km north-east of Takht-e Soleyman. On the highest part there are remains of a citadel (an area of 60 m by 50 m), dating to the Sassanian era, built from yellow sandstone. The explorations that have been carried out so far on the site indicate that the citadel would have contained another fire temple. Its orientation indicates a close relationship with Takht-e Soleyman.

https://www.visitiran.ir/attraction/takht-e-soleyman

Bam and its Cultural Landscape

Bam is situated in a desert environment on the southern edge of the Iranian high plateau. The origins of Bam can be traced back to the Achaemenid period (6th to 4th centuries BC). Bam developed at the crossroads of important trade routes at the southern side of the Iranian high plateau, and it became an outstanding example of the interaction of the various influences. The Bam and its Cultural Landscape represents an exceptional testimony to the development of a trading settlement in the desert environment of the Central Asian region. The city of Bam represents an outstanding example of a fortified settlement and citadel in the Central Asian region, based on the use mud layer technique (Chineh) combined with mud bricks (Khesht). The cultural landscape of Bam is an outstanding representation of the interaction of man and nature in a desert environment, using the qanats. The system is based on a strict social system with precise tasks and responsibilities, which have been maintained in use until the present, but has now become vulnerable to irreversible change.

Bam and related sites represent a cultural landscape and an exceptional testimony to the development of a trading settlement in the desert environment of the Central Asian region. It developed at the crossroads of important trade routes at the southern side of the Iranian high plateau, and it became an outstanding example of the interaction of the various influences. It is an outstanding example of a fortified settlement and citadel in the Central Asian region, based on the use of mud layer technique (Chineh) combined with mud bricks (Khesht).The cultural landscape of Bam is an outstanding representation of the interaction of man and nature in a desert environment, using qanats. The system is based on a strict social system with precise tasks and responsibilities, which have been maintained in use until the present, but has now become vulnerable to irreversible change.Bam is situated between Jebal Barez Mountains and the Lut Desert at 1,060 m above sea level in south-eastern Iran. The city was affected by the 6.5 Richter scale earthquake on 26 December 2003. More than 26,000 people lost their lives and a large part of the town was destroyed. Bam grew in an oasis created mainly thanks to an underground water management system ( qanats), which has continued its function until the present day. The principal core zone consists of the Citadel (Arg-e Bam) with its surroundings. Outside this area, the specified remains of protected historic structures include: Qal'eh Dokhtar (Maiden's Fortress, c. 7th century), Emamzadeh Zeyd Mausoleum (11th-12th centuries), and Emamzadeh Asiri Mausoleum (12th century). The Enclosure of the Citadel (Arg-e Bam) has 38 watchtowers; the principal entrance gate is in the south, and there are three other gates. A moat surrounds the outer defence wall, which encloses the Government Quarters and the historic town of Bam. The impressive Government Quarters are situated on a rocky hill (45 m high) in the northern section of the enclosure, surrounded by a double fortification wall. The main residential quarter of the historic town occupies the southern section of the enclosure. The notable structures include the bazaar extending from the main south entrance towards the governor's quarters in the north. In the eastern part, buildings include the Congregational Mosque, the Mirza Na'im ensemble (18th century), and the Mir House. The mosque may be one of the oldest built in Iran, going back to the 8th or 9th centuries, probably rebuilt in the 17th century. The north-western area of the enclosure is occupied by another residential quarter, Konari Quarter.

The beginnings of Bam are fundamentally linked with the invention and development of the qanat system. The technique of using qanats was sufficiently well established in the Achaemenid period (6th-4th centuries BC). The archaeological discoveries of ancient qanats in the south-eastern suburbs of Bam are datable at least to the beginning of the 2nd century BC. A popular belief attributes the foundation of the town itself to Haftvad, who lived at the time of Ardashir Babakan, the founder of the Sassanian Empire (3rd century BC). The name of Bam has been associated with the 'burst of the worm' (silk worm). Haftvad is given as the person who introduced silk and cotton weaving to the region of Kerman.

https://www.visitiran.ir/attraction/bam-its-cultural-landscape

Pasargadae

Pasargadae was the first dynastic capital of the Achaemenid Empire, founded by Cyrus II the Great, in Pars, homeland of the Persians, in the 6th century BCIts palaces, gardens and the mausoleum of Cyrus are outstanding. Pasargadae is the first outstanding expression of the royal Achaemenid architecture. The dynastic capital of Pasargadae was built by Cyrus the Great with a contribution by different peoples of the empire created by him. It became a fundamental phase in the evolution of the classic Persian art and architecture. The archaeological site of Pasargadae with its palaces, gardens, and the tomb of the founder of the dynasty, Cyrus the Great, represents an exceptional testimony to the Achaemenid civilisation in Persia. The Four Gardens type of royal ensemble, which was created in Pasargadae became a prototype for Western Asian architecture and design.

The dynastic capital of Pasargadae was built by Cyrus the Great in the 6th century BC with contributions from different peoples of the empire created by him. It became a fundamental phase in the evolution of the classic Persian art and architecture. With its palaces, gardens, and the tomb of the founder of the dynasty, Cyrus the Great, Pasargadae represents exceptional testimony to the Achaemenid civilisation in Persia. The 'Four Gardens' type of royal ensemble created in Pasargadae became a prototype for Western Asian architecture and design.

Pasargadae is located in the plain on the river Polvar, in the heart of Pars, the homeland of the Persians. The position of the town is also denoted in its name: 'the camp of Persia'. The core zone of the site is surrounded by a large landscape buffer zone. The core area contains many monuments: the Mausoleum of Cyrus the Great is built from white limestone around 540-530 BCE. The mausoleum chamber, on the top, has the form of a simple gable house with a small opening from the west. In the medieval period, the monument was thought to be the tomb of Solomon's mother, and a mosque was built around it, using columns from the remains of the ancient palaces. A small prayer niche ( mihrab) was carved in the tomb chamber. In the 1970s, during a restoration, the remains of the mosque were removed, and the ancient fragments were deposited close to their original location.

The Tall-e Takht refers to the great fortified terrace platform built on a hill at the northern limit of Pasargadae. This limestone structure is built from dry masonry, using large regular stone blocks and a jointing technique called anathyrosis, which was known in Asia Minor in the 6th century. The first phase of the construction was built by Cyrus the Great, halted at his death in 530 BCE. The second phase was built under Darius the Great (522-486 BCE), using mud brick construction.

The royal ensemble occupies the central area of Pasargadae. It consists of several palaces originally located within a garden ensemble (the so-called 'Four Gardens'). The colour scheme of the architecture is given by the black and white stones used in its structure. The main body of the palaces is formed of a hypostyle hall, to which are attached porticoes. The Audience Hall was built around 539 BCE. Its hypostyle hall has two rows of four columns. The column bases are in black stone and the column shafts in white limestone. The capitals were in black stone. There is evidence of a capital representing a hybrid, horned and crested lion. The palace had a portico on each side. Some of the bas-reliefs of the doorways are preserved, showing human figures and monsters. The Residential Palace of Cyrus II was built 535-530 BCE; its hypostyle hall has five rows of six columns. The Gate House stands at the eastern limit of the core zone. It is a hypostyle hall with a rectangular plan. In one of the door jambs is the famous relief of the 'winged figure'.

In later periods, Tall-e Takht continued to be used as a fort, whereas the palaces were abandoned and the material was reused. From the 7th century onwards, the tomb of Cyrus was called the Tomb of the Mother of Solomon, and it became a place of pilgrimage. In the 10th century, a small mosque was built around it, which was in use until the 14th century.

https://www.visitiran.ir/attraction/pasargadae

Soltaniyeh

The mausoleum of Oljaytu was constructed in 1302 12 in the city of Soltaniyeh, the capital of the Ilkhanid dynasty, which was founded by the Mongols. Situated in the province of Zanjan. The Mausoleum of Oljaytu forms an essential link in the development of the Islamic architecture in central and western Asia, from the classical Seljuk phase into the Timurid period. This is particularly relevant to the double-shell structure and the elaborate use of materials and themes in the decoration. Soltaniyeh as the ancient capital of the Ilkhanid dynasty represents an exceptional testimony to the history of the 13th and 14th centuries. The Mausoleum of Oljaytu represents an outstanding achievement in the development of Persian architecture particularly in the Ilkhanid period, characterized by its innovative engineering structure, spatial proportions, architectural forms and the decorative patterns and techniques.

As the ancient capital of the Ilkhanid dynasty, Soltaniyeh represents an exceptional testimony to the history of the 13th and 14th centuries. The Mausoleum of Oljaytu forms an essential link in the development of Islamic architecture in central and western Asia, from the classical Seljuk phase until the Timurid period. This is particularly relevant to the double-shell structure and the elaborate use of materials and themes in the decoration. It is outstanding by virtue of its innovative engineering structure, spatial proportions, architectural forms and the decorative patterns and techniques.